The labor force remains tight, wages are rising, and people are coming off the sidelines to find work, according to new data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) monthly Employment Situation Report. Highlights from the report include: the unemployment rate remained at 3.5 percent, matching the lowest rate since May 1969; nonfarm job gains were 145,000, bringing 2019’s total to 2.1 million; the U-4, U-5, and U-6 alternative measures of labor underutilization were all at series lows; and the employment-population ratio for prime-age women increased 0.3 percentage points to 74.4 percent, which is 3.1 percentage points above the November 2016 rate.

Over 2019, the United States added an average of 176,000 jobs a month. To put that growth into perspective, the U.S. economy needs to create around 70,000 jobs a month to keep pace with working-age population growth. Any employment growth above this level is typically from workers coming off the sidelines. With employment gains surpassing 100,000 in 34 of the 37 months since the 2016 election, and the economy adding jobs in each month, this is precisely what is happening under President Trump.

In the fourth quarter of 2019, 74.2 percent of workers entering employment came from out of the labor force rather than from unemployment, which is the highest share since the series began in 1990. This influx of workers has brought the labor force participation rate for prime-age adults (ages 25-54) up to 82.9 percent in December—1.6 percentage points above the rate in November 2016. Since the election, the prime-age labor force has expanded by 2.3 million people. From the start of the prior Administration’s expansion period until the 2016 election, the prime-age labor force shrank by 1.6 million.

With monthly payroll employment growth outpacing that required to maintain a stable employment-to-population ratio, employers are raising wages to attract and retain workers. December marks the 17th consecutive month that average hourly earnings growth for production non-supervisory workers has been at or above 3 percent. This average gain for workers shows how pro-growth policies that raise labor demand and incentivize employers to invest more in their employees have resulted in higher wage gains for historically disadvantaged Americans.

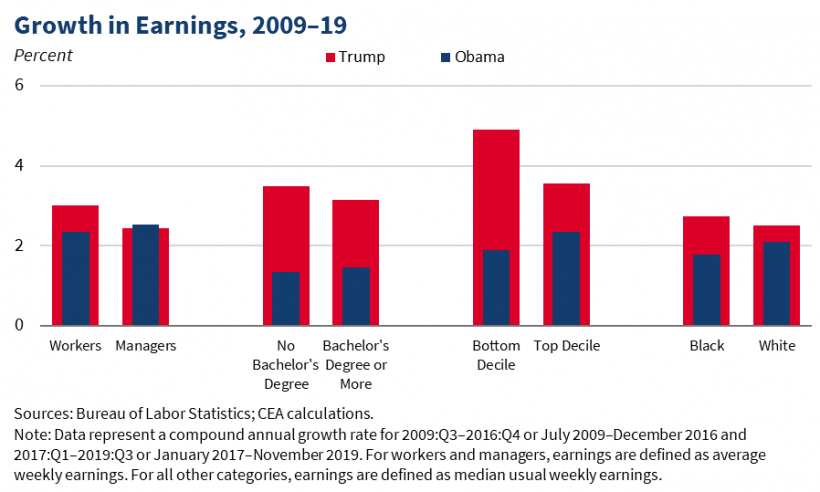

As shown in the figure below, since President Trump took office:

- Average wage growth for workers now outpaces wage growth for managers;

- Average wage growth for those without a bachelor’s degree now outpaces wage growth for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher;

- Average wage growth for individuals at the 10th percentile of the income distribution now outpaces wage growth for individuals at the 90th percentile;

- And average wage growth for African Americans now outpaces wage growth for white Americans.

These results are the opposite of those observed over the previous administration’s expansion period, where historically advantaged groups saw higher wage gains.

Few thought these labor market gains were possible before President Trump’s election. The years following the financial crisis were filled with worries that labor force participation had entered a permanent state of decline. Economists and political pundits alike claimed the United States had entered an era of “secular stagnation,” where slow job and wage growth would be the new norm. Now, the same skeptics wonder how long this impressive movement into the labor force can continue. Even with strong recent gains, the booming labor force has more room to grow.

In terms of labor slack, there are currently 5.8 million unemployed workers who are counted in the labor force. There are an additional 1.2 million marginally attached workers over 16 years old who are not counted in the labor force. Marginally attached refers to individuals who are not currently in the labor force but who want a job, are available to work, and have looked for work in the last year but not in the last four weeks (as they must do to count as unemployed).

If the prime-age labor force participation rate were to return to its pre-financial crisis level of 83.1 percent (December 2007), an additional 248,000 prime-age workers would be in the labor force. If prime-age participation were to return to its historic high of 84.6 percent (January 1999), an additional 2.1 million prime-age workers would be in the labor force. Between the 7 million people who are unemployed or marginally attached to the labor force, the 2.1 million people gap between today’s labor force participation rate and the historic high, and the natural growth in working-age population, U.S. labor force participation has a lot of room to expand before labor supply is exhausted.

Long-bemoaned trends in labor force participation over the past two decades are not policy-invariant, as the Trump Administration’s pro-growth policies continue supporting higher wages and more people entering the labor market. Thankfully, there is even more room for the job market to expand on the results of December’s Employment Situation Report. This is great news for the American economy—and for the millions of Americans who will be able to build better lives through work.