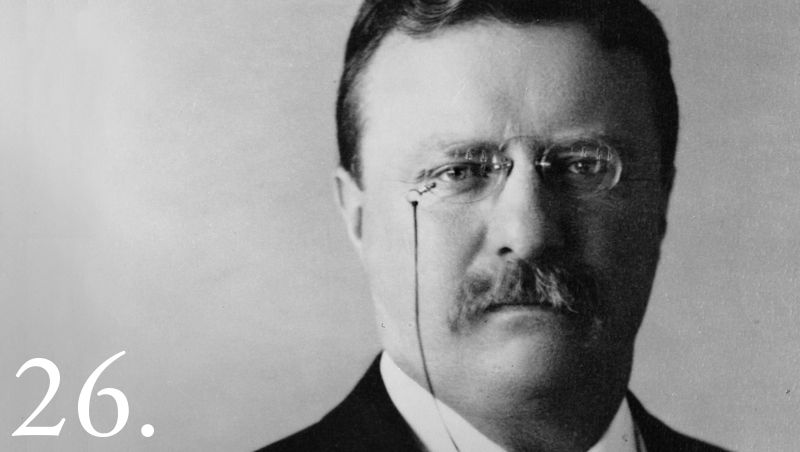

With the assassination of President William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, not quite 43, became the 26th and youngest President in the Nation’s history (1901-1909). He brought new excitement and power to the office, vigorously leading Congress and the American public toward progressive reforms and a strong foreign policy.

With the assassination of President McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, not quite 43, became the youngest President in the Nation’s history. He brought new excitement and power to the Presidency, as he vigorously led Congress and the American public toward progressive reforms and a strong foreign policy.

He took the view that the President as a “steward of the people” should take whatever action necessary for the public good unless expressly forbidden by law or the Constitution.” I did not usurp power,” he wrote, “but I did greatly broaden the use of executive power.”

Roosevelt’s youth differed sharply from that of the log cabin Presidents. He was born in New York City in 1858 into a wealthy family, but he too struggled–against ill health–and in his triumph became an advocate of the strenuous life.

In 1884 his first wife, Alice Lee Roosevelt, and his mother died on the same day. Roosevelt spent much of the next two years on his ranch in the Badlands of Dakota Territory. There he mastered his sorrow as he lived in the saddle, driving cattle, hunting big game–he even captured an outlaw. On a visit to London, he married Edith Carow in December 1886.

During the Spanish-American War, Roosevelt was lieutenant colonel of the Rough Rider Regiment, which he led on a charge at the battle of San Juan. He was one of the most conspicuous heroes of the war.

Boss Tom Platt, needing a hero to draw attention away from scandals in New York State, accepted Roosevelt as the Republican candidate for Governor in 1898. Roosevelt won and served with distinction.

As President, Roosevelt held the ideal that the Government should be the great arbiter of the conflicting economic forces in the Nation, especially between capital and labor, guaranteeing justice to each and dispensing favors to none.

Roosevelt emerged spectacularly as a “trust buster” by forcing the dissolution of a great railroad combination in the Northwest. Other antitrust suits under the Sherman Act followed.

Roosevelt steered the United States more actively into world politics. He liked to quote a favorite proverb, “Speak softly and carry a big stick. . . . ”

Aware of the strategic need for a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific, Roosevelt ensured the construction of the Panama Canal. His corollary to the Monroe Doctrine prevented the establishment of foreign bases in the Caribbean and arrogated the sole right of intervention in Latin America to the United States.

He won the Nobel Peace Prize for mediating the Russo-Japanese War, reached a Gentleman’s Agreement on immigration with Japan, and sent the Great White Fleet on a goodwill tour of the world.

Some of Theodore Roosevelt’s most effective achievements were in conservation. He added enormously to the national forests in the West, reserved lands for public use, and fostered great irrigation projects.

He crusaded endlessly on matters big and small, exciting audiences with his high-pitched voice, jutting jaw, and pounding fist. “The life of strenuous endeavor” was a must for those around him, as he romped with his five younger children and led ambassadors on hikes through Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C.

Leaving the Presidency in 1909, Roosevelt went on an African safari, then jumped back into politics. In 1912 he ran for President on a Progressive ticket. To reporters he once remarked that he felt as fit as a bull moose, the name of his new party.

While campaigning in Milwaukee, he was shot in the chest by a fanatic. Roosevelt soon recovered, but his words at that time would have been applicable at the time of his death in 1919: “No man has had a happier life than I have led; a happier life in every way.”

The Presidential biographies on WhiteHouse.gov are from “The Presidents of the United States of America,” by Frank Freidel and Hugh Sidey. Copyright 2006 by the White House Historical Association.

Learn more about Theodore Roosevelt’s spouse, Edith Kermit Carow Roosevelt.